From the London Review:

“Anglo-America’s dingy realities – deindustrialisation, low-wage work, underemployment, hyper-incarceration and enfeebled or exclusionary health systems – have long been evident. Nevertheless, the moral, political and material squalor of two of the wealthiest and most powerful societies in history still comes as a shock to some… every morning in the endless month of March, Americans woke up to find themselves citizens of a failed state. In fact, the state has been AWOL for decades, and the market has been entrusted with the tasks most societies reserve almost exclusively for government: healthcare, pensions, low-income housing, education, social services and incarceration.

Pankaj Mishra

The other dingy reality is that we use the police as a cordon sanitaire between us and the consequences of all of our social and political failures; the police keep the homeless out our minds; the mentally ill away from our door steps, the darker skin tones in their allotted neighborhoods and the desperately poor from stealing from a “middle class” teetering with economic precarity. While we have come to live without a general sense of prosperity, we cannot seem to relinquish our attachment to “order”.

Of course we can’t. We can sense that we are, collectively, a ticking time bomb. Today, American exceptionalism means extreme inequality of wealth, more guns than sense, abiding racism and a pathological distrust of collective problem solving. The way we police in the U.S. is inextricably bound up in the exploitative capitalism to which we as citizens have become resigned.

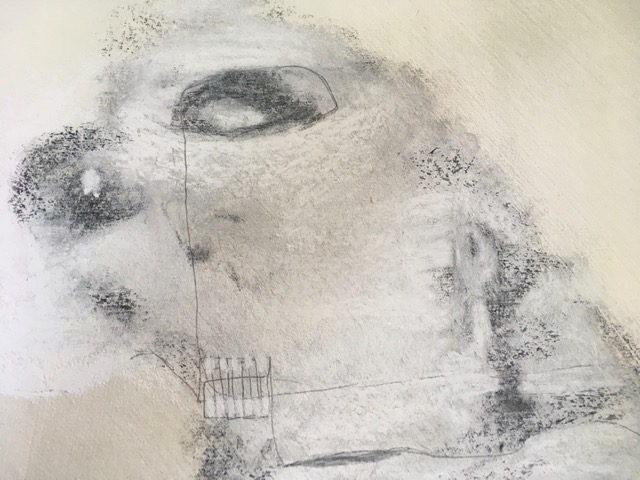

The police are to capitalism what neurotic or compulsive behaviors are to the psychoanalyst; symptoms of a (death) drive. In Freud’s words, (the drive)… is “like the grain of sand around which an oyster forms its pearl”.

The capitalist death drive is to accumulate, to acquire and to constantly rediscover that that no acquistion really satisifies, no level of profit is sufficient. Impelled by a dread of scarcity and the impoverished view that the only real “wealth” is private, Americans are frantic earners in a bleak zero sum landscape. If I don’t get it, someone else will. We accept that there are “winners and losers”. We accept that folks for whom cost-benefit analyses are difficult, impossible or irrelevant tend to get pissed off when they perceive themselves to be left behind. They are wont to behave in ways that disrupt the “order” that dispossesses them.

The state proscribes violence to its citizens. Not as Freud pointed out, because it disapproves of violence, but because it wants the monopoly on violence. The majority Black population of Minneapolis distrust their police greatly but cannot imagine their absence. In the USA, we have created our own monsters; we are the jailers and the jailed.

As with the neurotic, dysfunction continues until the drive is recognized (and re-addressed). Until we contend with ravening capitalism, our policing will remain unchanged.