(This being the last of three posts “inspired” by David Brook’s column, “The Costs of Relativism“)

David Brooks is a “conservative intellectual”. He can don the trappings of post Enlightenment social science (“recurring feedback loops”) and he can write marvelous and empathic sentences such as these:

The profiles from high-school-educated America are familiar but horrific….The first response to these stats and to these profiles should be intense sympathy. We now have multiple generations of people caught in recurring feedback loops of economic stress and family breakdown, often leading to something approaching an anarchy of the intimate life.

David Brooks, being human, makes careful judgements about how to compose a column for his own purposes. His misdirection is artful. He doesn’t want to define “relativism”; he merely replaces it with “non-judgmental”. (In my previous post, I argued that human “non-judgementalism” is an oxymoron; that being without judgement is not a human possibility.) Brooks wants to leave the concept vague and then taint it by associating it with bad outcomes, despair and abuse. He wants the word “relativism” to unsettle us.

Brooks knows that he cannot explain (in 800 words) how “R” (relativism) caused “P” (poor people’s poor behavior) but by being vague he allows his readers to fill in the causal blanks. He knows he cannot forge that causal link and he knows that he doesn’t need to because he is blowing the dog whistle of a specific kind of judgementalism. Hear the whistle blow:

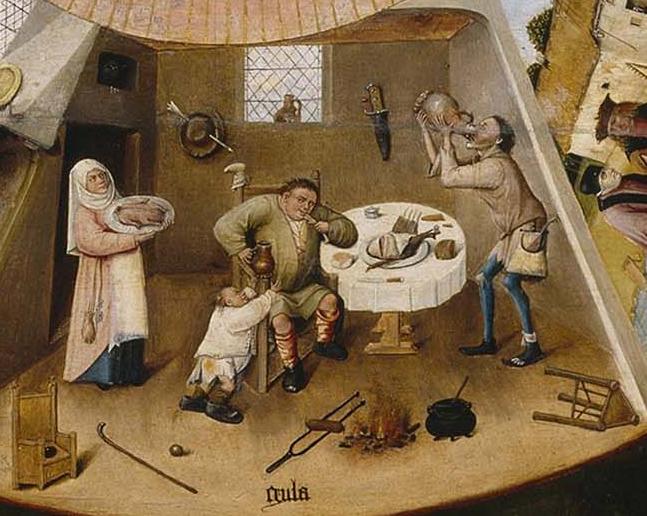

Are you living for short-term pleasure or long-term good? Are you living for yourself or for your children? Do you have the freedom of self-control or are you in bondage to your desires?

Republicans think poor people are to blame for their own poverty (their bad behavior is just another symptom of their insufficiency). Republicans do not believe in “socio-economic” forces*. They only believe in individual moral agency (or the lack thereof). When Republicans hear an expression like “structural poverty”, they also hear an excuse being offered. When Republicans hear “over 400 years of institutional racism”, they also hear responsibility being lifted from an immoral, undeserving agent. This is the politics of sin wherein true believers, without reflection, project their own private internal truths onto others. They feel that what is true for themselves must be true for others. In this “world view”, causality is not a problem. Sins are certain and their effects inevitable.

It is to this stance of self-certainty that David Brooks panders. None of us are without judgement but we are all free to adopt a stance toward our own judgements. The person with relativist inclinations will make an effort to periodically doubt her own certainties, employ critical thinking and engage her empathy in an effort to improve her understanding of other people. The audience to whom David Brooks is whistling seeks the reassuring certitude of fundamental grounds. David Brooks is often labeled a “conservative intellectual”. This label, in his case, is also an oxymoron because you cannot exercise your intellect by staying in one certain place. David Brooks and his fans are too timid to tolerate the critical examination of their own cherished and parochial judgements.

*Republicans have decided to believe in the “market” because they have mythologized it; they have anthropomorphized and then deified the “market” by endowing it first with sentience and agency and then, ironically enough, with transcendent judgement.