The Little Owl, A. Durer

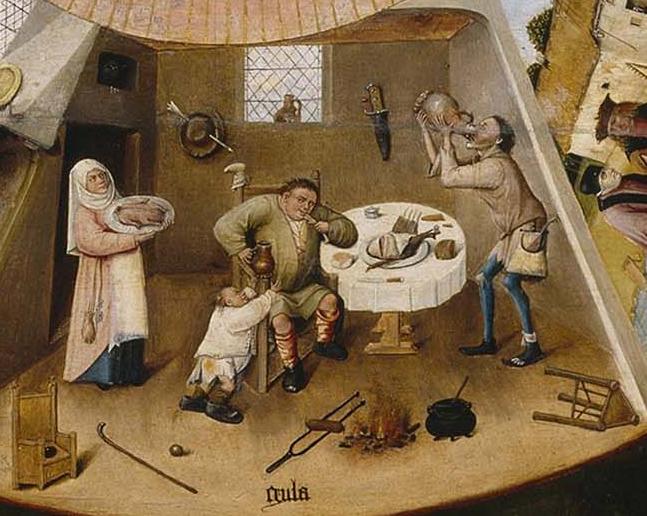

ISIS is beheading Yezidis, Bokul Harum is kidnapping schoolgirls and white Americans are screaming at busloads of children. Most people would agree that these are all extreme behaviors which are, at the very least, immoral. These perpetrators are all zombies; they no longer view their victims as thinking, feeling moral entities. How did they get that way? Could I ever act that way? In earlier posts about climate change I wrote that what we think we “know” about climate change is inextricably bound up with the belief systems we hold profoundly dear. If the cognitive balance between knowing and believing is fluctuant, what does this suggest about the relationship between knowledge and morality?

What do we need to “know” (about ourselves and the world) in order to feel like we are moral entities? We need to know that morality is not character; it is not just how we happen to BE, it is how we think and decide to act. The fundamental moral question -“What should I do?“- makes no sense without our perception that we have a choice between one action and another. Morality then is an activity in which we engage. We think of ourselves as beings to whom moral concepts apply and and we see ourselves as accountable. We create ourselves as moral beings by making choices and acting on those choices and we interact with others as if they are also self directed agents. While I believe that life is a moral venture, for me, the really interesting questions begin when I ask myself, at what level DO I GET TO DECIDE?

Richard Dawkins recently issued some Tweets about rape and Palestine that elicited some strong reactions. His defense in the Huffington Post is simple. His tweets were not interpreted logically. He goes on to decry that

some of us may be erecting taboo zones, where emotion is king and where reason is not admitted; where reason, in some cases, is actively intimidated and dare not show its face. And I regret this. We get enough of that from the religious faithful.

According to Dawkins, a true moral philosopher with “a love of reason” will not fear to tread where reason leads. Dawkins makes a lovely logical point (“If I say A is worse than B, I am NOT endorsing B“) but his larger issue is the unwillingness of some people to endure some discomfort in the pursuit of reasoned discourse. Clearly, Dawkins sees reason as a counterpoise to emotion (and by extension a counterpoise to “the religious faithful”). Reason is the exalted tool that will lead us to “truth”; a notion right out of the Enlightenment. Noting that Dawkins’ immediate goals in this instance are polemical, it should be pointed out that the concept of reason has changed somewhat since the Enlightenment.

Twentieth century history and anthropology teach us that the contingent facts of our race, gender, class and ethnicity predetermine much of who we are. We are not radically free (e.g., I am a white, North American middle class male. I cannot become an Ibo tribeswoman). In a post appropriately titled, “How Politics Makes Us Stupid”, Ezra Klein cites research that indicates that “individuals subconsciously resist factual information that threatens their defining values.” Behavioral economics is teaching us that “the rational man” of neoclassical economics is a chimera (at best). Reasonable people make economic decisions on the basis of rules of thumb, stereotypes and cultural canards. Vagaries of affect are inextricably bound up in our assessments of risk and how we value time (profit now versus profit later). Empirical studies have repeatedly shown that we all have “implicit biases” that guide our judgements but of which we are not consciously aware. Attachment theory tells us (with increasing support from neuroscience) that the earliest dyadic exchanges between mother and infant through gaze and touch will shape the rest of our psychic and social lives in primal, unconscious ways. The neuroscientist Antonio Damasio argues that emotions are not opposed to reason. Emotions are not unruly beasts to be saddled by reason but are in fact the substrate of all cognition.

Another small indicator that reason (logic and critical thinking) is just the tip of the cognitive iceberg may be seen in how we attribute causation to human behavior. We all tend to attribute the genesis of human behavior either to “character” or as a response to the external world. The interesting fact is that we are far more likely to see other people’s behavior as caused by character whereas we will more likely view our own behavior as being prompted by the outside world. We impute causation to disposition because 1) we can’t necessarily see the environmental factors prompting some one else’s behaviors and 2) (more importantly) not one of us likes to caricature ourselves as a thin set of statistically likely responses.(I am not hopping about and yelling because I am needy and want attention, I have been stung by a bee.) We experience our own self as a “neutral” locus of awareness (simply, “who we are”) that reacts to our environment. So, when we face moral choices in our interactions with others are we really understanding their motivations?

Sullied as it is by all these “un-reasonable” forces, what role is left for reason in morality? Does any one of us ever make a rational decision about what we ought to do?

To be truly moral (and to be truly reasonable) requires more activity than simply deciding upon a choice. To be truly moral we need to hold a mirror to ourselves, to bring to awareness the patterns of behavior to which we are prone and look for the warp of our affect even when we are following a weft of reason. To be truly moral means recognizing that the other free agents with whom we interact are also beings whose ability to engage in reasoned discourse is as circumscribed as our own. Professor Dawkins is absolutely right in placing enormous importance on reasoned discourse because it is only through discourse with others that we occasionally can see ourselves from the outside. Dr. Dawkins might have more productive conversations with the “religious faithful” if he thought more about thinking itself.

Even if reason is an infected tool, it is the only scalpel we have available to us.