Driving home from work during the Republican convention, I heard an NPR interview with a Young Republican who was asked how she would explain the basic Republican philosophy to other young people in a way that they would understand. She replied immediately that a smart phone is the ideal metaphor: it is the product of entrepreneurs and it empowers each person to make choices and connect with the world. Hers was a very “normal” American take on reality: the small “freedoms” of the marketplace are wedded to the American veneration of a self-seeking individualism.

In his seminal 1958 essay, Isiah Berlin contrasts the small “freedoms” I have been talking about with another kind of “Freedom” which is more generative. A capital “F” freedom is not just freedom from an external constraint, but the liberty to affect the context of one’s choices and in so doing exercise positive control over your own life. Having the “Freedom” to achieve ones own ends has both an internal, personal aspect and an external, collective dimension.

Personally, I must have the “Freedom” to contend with my own self…my fears, my passions and the state of my education… in order realize my own potential and get where I want to go. In the social and political sphere, I may need to become an actor upon the world rather than just a passive consumer. If so, I will need the larger “Freedom” to participate in collective decision making. Do I have the “Freedom” to help generate a social or political context that is more favorable to my self-realization? Am I “Free” to start my own political party? Can I join a union and improve my workplace? Or, are these larger “Freedoms” foreclosed to me? Am I, or are my fellow citizens, hindered in our efforts to realize our individual potential because of the color of our skins? the crushing weight of student debt? the dearth of middle class jobs where we live?

A key difference between the two “freedoms” is that one requires a longer attention span than the other. Going with the smart phone metaphor, it requires little expenditure of attention to log on to a cell and compare college web sites. You have the “Freedom” to acquire an education and the “freedom” to become an indentured servant as a result. Though you are also “Free” to campaign for affordable education, that entails politics; the messy and time consuming practice of bumping into other people with different ideas of what “F(f)reedom” should look like.

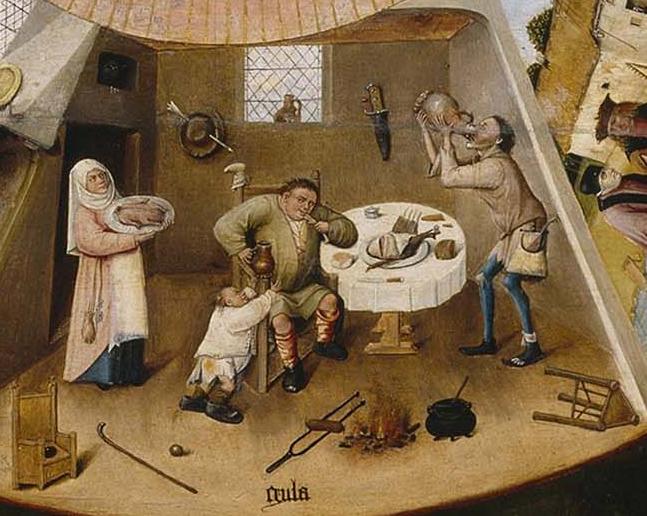

We now live in a new kind of market-created culture that fights to capture every shift of our attention; however fleeting. A new bright and shiny object is always available to bait our attention because there is a market creating that bait and tailoring that bait ever more precisely to each user’s tastes. I am a grandfather who earned a degree in Anthropology 35 years ago. A recent ad on my Facebook page offered me a t-shirt that reads “Always trust a Grandpa with an Anthropology degree”. What you will look at tomorrow on the Internet has already been predicted and sold.

At one level, all of these bright shiny objects are the same, they are all potential clicks. Most of us know (at some level of consciousness) that Donald Trump is where he is today because he is clickbait. He knows how to be clickbait. He didn’t need Jeb Bush’s advertising war chest because he knew how to propagate exabytes of self-exposure for free. Thoughtfully considered and detailed public policy plans are not bright and shiny objects. A click on Trump, Kardashian or U.S. trade policy are all the same to the click-market. Content or the meaning of the content does not matter; merely the number of clicks. The algorithms didn’t judge Donald Trump, they merely propelled him to our attention. The more attention Trump got, the more of him we were offered; a feed back loop that had the result of giving him an illusory dimensionality.

I am hardly the first person to notice that Donald Trump is particularly suited to be where he is today. Trump doesn’t need multi-dimensional policy statements because there is really only one bright and shiny ornament on his policy tree; America is no longer great. It matters little that blaming trade agreements and immigration is simplistic and panders to ignorance and racism. The fear and dissatisfaction he is tapping into is very real.

The “free market” has failed to deliver. It has failed in rural America where economic opportunity is decreasing and opioid use is increasing. The “free market” has failed the Rust Belt where the human dislocation from 30 years of globalization and technological change has been allowed to fester. The “free market” has kept real wage growth stagnant for decades. The gloom of living paycheck to paycheck is pervasive in America.

But this is our brave new neoliberal world. The ephemeral can be monetized-“That’s only natural!” . We need not bother our pretty little heads thinking about “Freedom”- “Let the market sort it out!”. But when the free market’s outcomes are shitty, where do we turn? To a bright and shiny strongman who will let us keep our shallow freedoms (our smart phones, our guns, our Social Security). He will tell us what to do thereby relieving us of the fundamental Freedom to think for ourselves and shape our own political and social destinies.