Ta Nahesi Coate’s long essay “Between the World and Me” is a work of profound humanism. Toni Morrison’s jacket blurb says the book:

“is visceral, eloquent and beautifully redemptive. And its examination of the hazards and hopes of black male life is as profound as it is revelatory. This is required reading.’

Morrison is merely being accurate; this being the rare case where the jacket blurb has to undersell to remain credible.

Coates is an anthropologist in his own land; the structural Outsider observing the American “Dream” as it is beamed into his redlined neighborhood. This essay to his 15 year old son limns his personal journey as he has tried to come to terms with the disjunctions between how the world of “the Dream” is supposed to be and how it is actually lived by those it purposefully excludes.

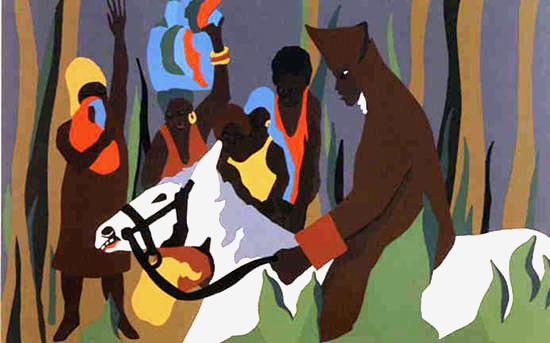

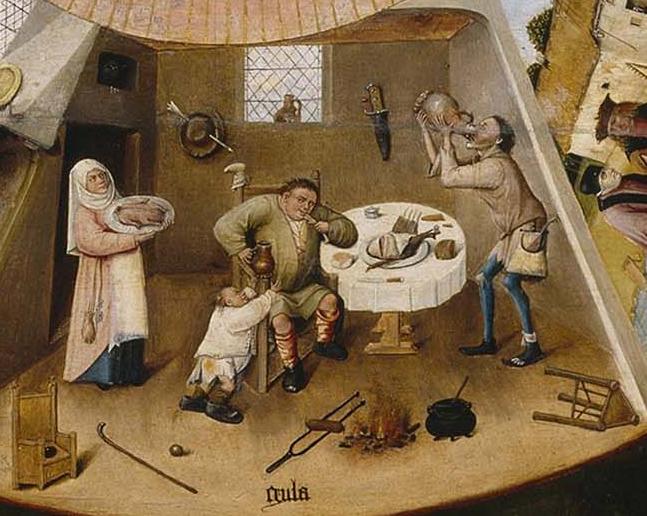

Raised outside the African-American religious tradition, he is instead taught by his grandmother as a grade schooler to write and to use his writing to “ruthlessly interrogate” himself. He learns early that there are disjunctions between his own feelings and actions; he learns early about self-deception and mixed motives. He grows up in the physical peril of North Baltimore. Though he leaves Baltimore, goes to Howard University and becomes a senior editor at the Atlantic Monthly, he cannot escape physical peril because he is a black male in the America of Ferguson, Missouri. This is the America that has been built upon 250 years of plunder beginning with slavery, through sharecropping and Jim Crow, to redlining, “school choice” and the carceral state. Coates is explaining to his son that America has nurtured the idea of “race” in order to ensure that a ready supply of the “other” is available for plunder. The abiding American chestnut that social inequality can be cured by a little more will power on the part of the victims allows Americans to ignore economic realities* and thereby cling fast to their moral exceptionalism.

This is not an essay about politics or the voluntarism of political strategy. Coates is not telling his readers how to respond. He is using the tools of the Enlightenment; empirical observation, a respect for history and his own self-aware critical faculties to identify the institutions (cultural, political and economic) that are arrayed against his son. Even positive reviews of the book have not been able to repress the urge to suggest that the vision Coates paints for his son is too bleak, too fatalistic and that he does not credit “the progress that has been made”. Such observations fail to grasp why Toni Morrison calls this book “redemptive”.

Coates takes an unflinching look at America. He is disappointed by the enduring gap between who we say we are and how we behave. Though he is not optimistic, he urges his son to struggle:

Struggle for the memory of your ancestors. Struggle for wisdom…Struggle for your grandmother and grandfather, for your name. But do not struggle for the Dreamers. Hope for them. Pray for them if you are so moved. But do not pin your struggle on their conversion.

Can you struggle without Hope? For Coates, Hope resides in the act of wrestling with himself in the world. Hope is a creature of reason. Only by thinking critically can you imagine a different world. The question “What’s wrong with this picture?” leads to imagining other ways “this picture” can look. Like Abraham who, with trembling limbs, wielded his reason and sense of justice against God himself; Coates stands before the omnivorous power of “the Dream”, calls it out, and redeems his freedom.

*Also known back in the day as “property relations”